Strengthening Children’s Access to Justice in the Pacific Islands

by Leisha Lister

Indira Rosenthal outside the High Court of the Solomon Islands

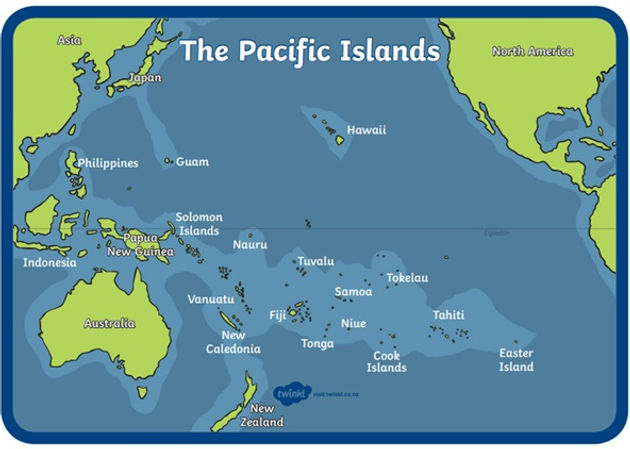

The Pacific Islands are as diverse as they are beautiful, with cultures, languages, and traditions that shape every aspect of daily life - including access to justice. But this diversity also brings unique challenges. Many countries in the region are made up of widely scattered islands, making it difficult for children to physically access courts, legal aid, or police services. In some cases, the journey itself is a barrier, especially for those living on outer islands.

The legal landscape is equally complex. Most Pacific countries operate under plural legal systems, where formal state-based law coexists with customary law. While customary systems are deeply respected and play an important role in resolving disputes, they don’t always align with international standards for child rights. Sometimes, serious cases like sexual violence are handled informally, with a focus on reconciliation rather than accountability or the protection of the child.

Cultural norms further shape how justice is accessed. In tightly knit communities, respect for elders and social cohesion can discourage families from reporting crimes, especially if the perpetrator is a respected figure. Children’s voices are rarely heard in legal proceedings, and low levels of legal literacy make it even harder for families to navigate the system.

Access to justice is more than a legal right - it’s a lifeline for children who have experienced harm or are in conflict with the law. When justice systems are hard to reach, under-resourced, or not designed with children in mind, vulnerable children fall through the cracks. This is especially true for children with disabilities, who face additional barriers and are often invisible in planning and service delivery.

Natural disasters are common in the Pacific and can disrupt justice and child protection services even further, leaving children at risk when they are most vulnerable.

The Project: A Regional Stocktake

UNICEF Pacific’s recent Child Protection Program Strategy (2023–2027) set out to assess the state of child justice in five countries: Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and Samoa.

To support this strategy, for the past 18 months, Child Frontiers associates Leisha Lister and Indira Rosenthal have engaged with government officials, civil society, and faith-based organizations to get a clear picture of what’s working, what’s not, and what needs to change.

Their review produced:

-

Five detailed country reports, each mapping out key challenges and opportunities for reform.

-

A two-day stakeholder forum, where findings were shared and a roadmap for action was developed.

-

Model Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and training packages tailored for local adaptation.

-

Specific legal advice and practical toolkits, such as a Good Practice Toolkit for Vanuatu’s prosecutors and a trainers’ manual for Kiribati’s police.

A Roadmap for the Future

The project didn’t just identify problems, it offered practical solutions. Our team developed model Standard Operating Procedures, training materials, and recommendations tailored to each country’s context. These tools are already being used to train judges in Fiji, guide prosecutors in Vanuatu, and support police in Kiribati.

The reviews confirm that while progress has been made, child justice systems in the Pacific are still unevenly resourced and underdeveloped. To build systems that truly protect children’s rights, governments and partners must:

-

Enact and enforce comprehensive child protection legislation.

-

Invest in child-sensitive procedures, training, and infrastructure.

-

Strengthen data systems and legal literacy programs.

-

Ensure children with disabilities are included in justice planning and delivery.

Collaboration is Key

No single agency can do this alone. Sustained collaboration between governments, civil society, and development partners is vital. By aligning national efforts with international child rights standards, while respecting local realities, the Pacific can establish robust justice systems that are accessible and responsive to all children. For the children of Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and Samoa, these reforms are more than policy - they are a promise of protection, voice, and hope for a fairer future.