Factors influencing and affecting Child Marriage Practices in Pakistan, following environmental disasters

by Dahye Yim, Ben Cislaghi

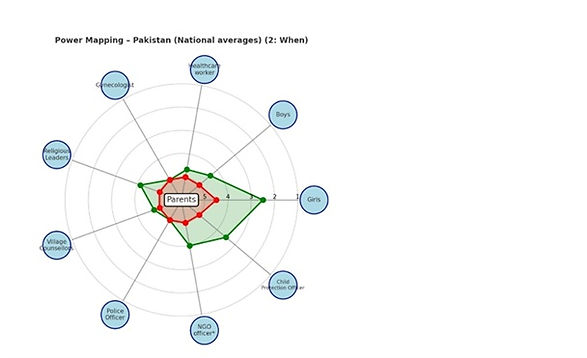

Power Mapping

Child marriage is a longstanding issue in Pakistan, affecting 18.9 million girls who are married before the age of 18. This year, our team conducted qualitative research for UNICEF Pakistan to explore how communities across the country understand, justify and challenge child marriage. The study looked at how gender roles, family expectations, poverty, class, ethnicity, and regional differences influence the prevalence and experience of child marriage.

The research covered Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Baluchistan, chosen to reflect both high and low prevalence of child marriage. Using interviews, focus group discussions and participatory workshops, the team gained rich insights into social norms and gender and power dynamics. Two methods in particular, power mapping and social network analysis, offered real insights into who holds decision-making powers and who influences marriage decisions.

The team used a power mapping tool to explore how children and adults understand and describe decision-making powers around marriage. Separate groups of girls and boys (aged 12-7) and with younger and older women and men (18-34 and 35-60), discussed five key areas:

1) Who a child should marry;

2) When the marriage should happen;

3) The type of wedding to celebrate;

4) The duration of the engagement; and

5) Whether the marriage should continue or end if problems arise.

Participants were asked to show two things: how decisions are made now (the reality) and how they believe decisions should be made (aspirations). They chose from five options on a scale ranging from “child alone” to “parents alone”, first individually and then together as a group. Figure 1 shows power mapping for boys in Punjab.

Figure 1 shows power mapping for boys in Punjab.

The radar diagram of the power map (illustrated) illustrates how different groups assessed the power of parents in decision-making (in red), compared to their preferred level of power (in green).

Across the different groups, girls - who were excluded from the decision-making process - expressed the strongest desire for greater autonomy, especially regarding partner choice, timing, and the right to end a marriage if things go wrong. Boys, in contrast, preferred consultation rather than full control, reflecting an acceptance of existing structures that position them as partial participants in decisions.

“The decision should be 100% the girl’s”

“It is her life, and she knows when she is ready for marriage”

quotes from girls in Baluchistan workshop

Qualitative social network analysis

This method was used to identify who, within the child’s network, influences decisions about their marriage. In each village, a girl and a boy who had been married before age 18, described their social network, the people they rely on for various forms of support, and those who played a key role in their marriage process. We then interviewed 4-5 people nominated by the child, and asked a similar set of questions. These networks revealed layers of influence, including key influencers and decision-makers, and showed how marriage decisions emerge from complex interactions among relatives, kinship groups, and community members.

In Baluchistan, a boy’s network (Figure 3) demonstrated how his extended family honoured the late mother’s last wish, considered culturally essential, by arranging his marriage to her cousin. The mother appeared at the centre of the network and was widely recognised as the primary decision-maker

In Punjab, a girl’s network (Figure 4) showed the strong symbolic power of her maternal grandmother, whose influence shaped the decisions of the father and the husband. Despite the father appearing to lead the process, interviews revealed that both he and the husband acted in accordance with the grandmother’s wishes regarding partner choice and timing.

These tools revealed the strong influence of kinship networks, entrenched gender and age hierarchies, and the limited space children have to express their preferences. Importantly, they also highlighted opportunities for change by showing where aspirations for more equitable decision-making already exist.

The use of these participatory tools revealed hidden dynamics and new possibilities for change. Our Child Frontiers’ research team has described how using creative approaches allowed children and adults to express feelings, hopes, and contradictions often left unsaid.

Dahye Yim, part of our research team, reflected, “I hope this study helps people understand child marriage in Pakistan through many different lenses — gender, tradition, class — and that the findings inspire communities to create solutions that fit their own context.”

The team is now developing a roadmap and advocacy/action brief, which UNICEF will take to stakeholders and key informants to discuss strategies to support more equitable decision-making for children.